Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) and modern humans (Homo sapiens) are two distinct species that share a common ancestor and lived alongside each other for thousands of years. Despite their extinction around 40,000 years ago, Neanderthals have left a significant genetic legacy within modern human populations. Advances in DNA analysis have revealed surprising insights into their biology, behavior, and interactions with modern humans. This article explores what our DNA tells us about Neanderthals and how their genes continue to influence us today.

1. Who Were the Neanderthals? An Overview of Our Closest Relatives

Neanderthals were a group of archaic humans who lived in Europe and parts of Asia from about 400,000 to 40,000 years ago. They were well-adapted to the cold environments of the Ice Age, with robust bodies, large noses, and short limbs to conserve heat. Their brains were slightly larger than those of modern humans, suggesting complex cognitive abilities.

Neanderthals were skilled hunters and toolmakers. They used sophisticated tools, controlled fire, and lived in complex social groups. Evidence suggests they also buried their dead and may have had some form of symbolic or artistic expression. Despite these advanced behaviors, they eventually disappeared, leaving modern humans as the sole surviving species of the genus Homo.

The relationship between Neanderthals and modern humans was a topic of speculation for many years. Were they a distinct species, or were they simply a different form of human? The answer to this question began to take shape with the advent of ancient DNA analysis.

2. Unraveling the Genetic Code: The Neanderthal Genome Project

The breakthrough in understanding our connection with Neanderthals came in 2010 when scientists successfully sequenced the Neanderthal genome. This monumental achievement was led by a team of researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, under the guidance of Svante Pääbo. By extracting DNA from Neanderthal bones and comparing it with modern human DNA, they were able to reveal a surprising discovery: Neanderthals and modern humans had interbred.

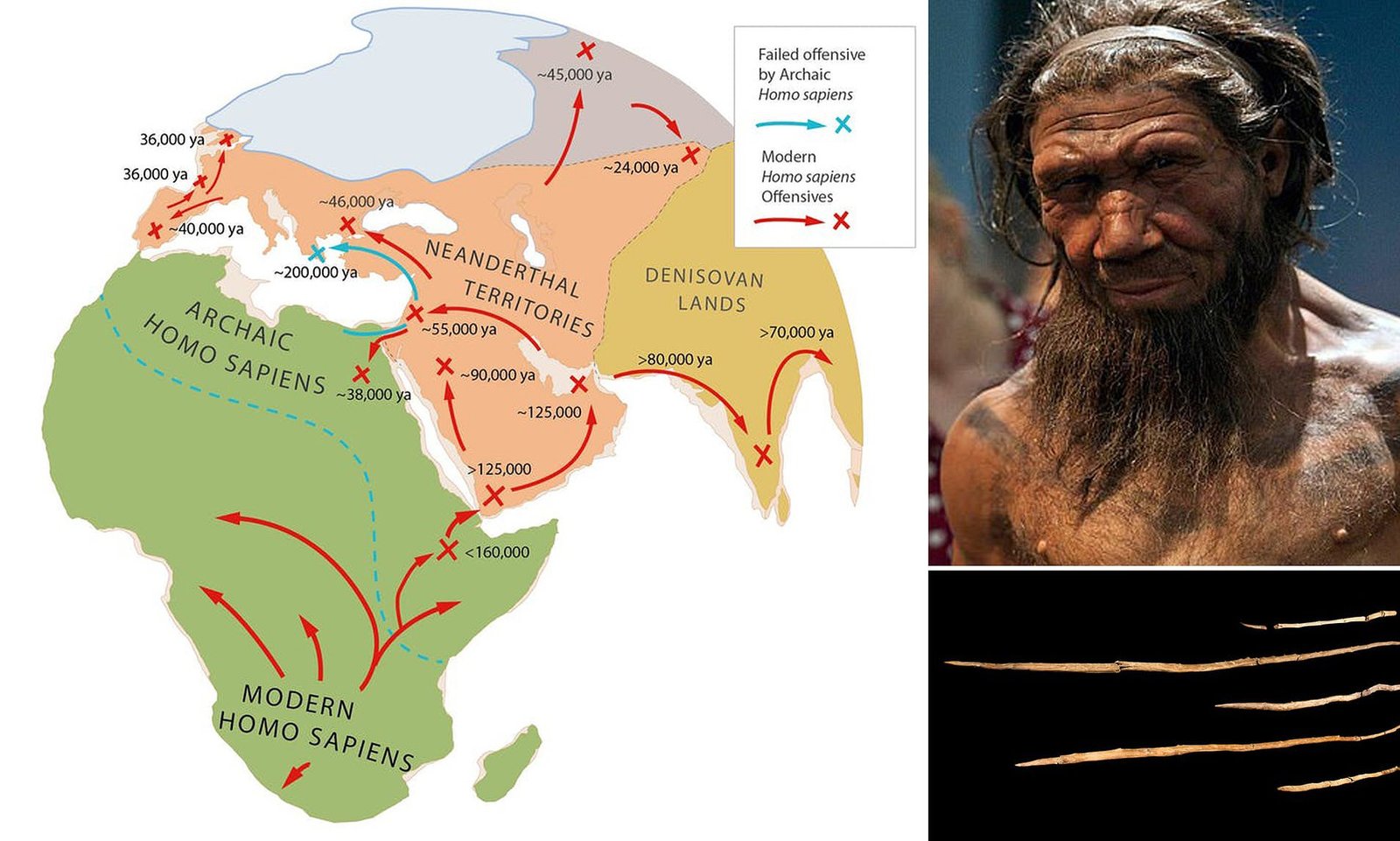

The analysis showed that Neanderthals contributed about 1-2% of the genome of non-African modern humans. This interbreeding likely occurred around 50,000 to 60,000 years ago, as modern humans migrated out of Africa and encountered Neanderthals in the Middle East and Europe. The presence of Neanderthal DNA in modern humans has reshaped our understanding of their relationship and blurred the lines between species.

3. Shared DNA: What We Inherited from Neanderthals

The Neanderthal DNA that modern humans carry is not randomly distributed but is concentrated in specific regions of our genome. These inherited genes influence various aspects of our biology, health, and even behavior. Some of the key areas influenced by Neanderthal DNA include:

- Immune System: Neanderthal genes have been linked to the strength and response of our immune systems. They may have helped early modern humans adapt to new pathogens as they spread into Neanderthal territories. However, these same genes are also associated with a higher risk of autoimmune disorders, such as lupus and Crohn’s disease.

- Skin and Hair Characteristics: Neanderthal DNA contributes to variations in skin and hair color, as well as the ability to tan. These traits likely provided advantages in adapting to different climates and levels of sunlight.

- Metabolism and Fat Storage: Certain Neanderthal genes are associated with fat metabolism and how the body stores fat. These adaptations may have been beneficial in cold environments but could predispose modern humans to conditions like obesity and type 2 diabetes in contemporary settings.

- Behavior and Brain Development: There is evidence that Neanderthal genes influence aspects of brain structure and function, including susceptibility to conditions like depression and addiction. However, the precise impact of these genes on behavior and cognition remains an active area of research.

4. Neanderthal Extinction: Why Did They Disappear?

Despite their advanced capabilities and close interactions with modern humans, Neanderthals went extinct around 40,000 years ago. The reasons for their disappearance are still debated, but several factors likely contributed:

- Competition with Modern Humans: As modern humans spread into Europe and Asia, they may have outcompeted Neanderthals for resources. Modern humans likely had better tools, more complex social networks, and perhaps more adaptable survival strategies.

- Climate Change: Neanderthals were adapted to cold environments, and rapid climate changes during their time may have disrupted their habitats and food sources. While modern humans were more adaptable and could rely on broader social networks and technology, Neanderthals may have struggled to cope with these changes.

- Interbreeding and Assimilation: It’s possible that rather than being completely wiped out, some Neanderthals were absorbed into the growing population of modern humans through interbreeding. Their genetic legacy in modern humans suggests that they did not entirely disappear but were assimilated.

5. Neanderthals vs. Modern Humans: Cognitive and Behavioral Comparisons

One of the most intriguing aspects of Neanderthals is how similar they were to modern humans in terms of behavior and cognition. They made sophisticated tools, used fire, hunted cooperatively, and possibly even created art. However, there were some notable differences that may have contributed to their eventual extinction.

- Tool Use and Technology: While Neanderthals made complex tools, their technology remained relatively static over long periods. In contrast, modern humans showed rapid innovation, developing new tools and techniques quickly. This technological flexibility may have given modern humans an edge in survival.

- Social Networks: Modern humans likely had larger and more complex social networks than Neanderthals. This would have allowed them to share information, resources, and innovations more effectively. Larger social groups could also provide better support during times of scarcity or conflict.

- Language and Communication: The extent of Neanderthal language abilities is still debated, but modern humans’ capacity for complex language and symbolic thought would have facilitated more effective communication and coordination. This could have been a crucial advantage in hunting, planning, and social organization.

6. The Denisovan Connection: Another Piece of the Puzzle

In addition to Neanderthals, another group of archaic humans, the Denisovans, interbred with modern humans. Denisovans are known only from a few fossils found in Siberia, but their genetic legacy is present in modern populations, especially in Melanesians and Indigenous Australians, who have up to 5% Denisovan DNA.

This discovery has expanded our understanding of the interactions between different human groups during the Pleistocene era. It suggests that modern humans, Neanderthals, and Denisovans were not isolated species but part of a complex web of interbreeding and gene flow. This genetic mixing has contributed to the diversity and adaptability of modern humans.

7. Modern Humans and Neanderthal DNA: The Impact on Health and Disease

While Neanderthal DNA has provided some beneficial adaptations, it also has implications for health and disease in modern populations. For example, Neanderthal variants have been linked to increased risks of certain conditions, such as:

- Autoimmune Disorders: As mentioned earlier, Neanderthal genes related to immune function can increase the risk of autoimmune diseases. These conditions occur when the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues.

- Allergies and Asthma: Some Neanderthal genes are associated with heightened immune responses, which may predispose individuals to allergies and asthma. This heightened sensitivity could have been advantageous in environments with new pathogens but can lead to overactive immune responses in modern settings.

- Mental Health: There is evidence that Neanderthal DNA may influence mental health conditions, including depression and mood disorders. The precise mechanisms are still being studied, but these findings suggest that our genetic legacy from Neanderthals can impact our psychological well-being.

8. What We’ve Learned: The Legacy of Neanderthals in Modern Humans

The study of Neanderthal DNA has revolutionized our understanding of human evolution and revealed a more complex picture of our ancestry. Far from being a separate, inferior species, Neanderthals were capable, intelligent, and adaptable. Their genetic contribution to modern humans has helped shape who we are today, influencing our biology, health, and even aspects of our behavior.

As research continues, we will likely discover even more about how Neanderthal genes impact modern human populations. This knowledge not only helps us understand our past but also offers insights into human biology and evolution that can inform medicine and health.

Conclusion: Neanderthals and the Human Story

Neanderthals were not just evolutionary dead ends but an integral part of the human story. Their interactions with modern humans and the genetic legacy they left behind have profoundly shaped our species. By studying Neanderthal DNA, we gain a deeper appreciation of the complex web of interactions that have made us who we are today.

FAQs

Q1: How much Neanderthal DNA do modern humans have?

Non-African modern humans carry about 1-2% Neanderthal DNA. This genetic legacy is the result of interbreeding between Neanderthals and early modern humans around 50,000 to 60,000 years ago.

Q2: Do all humans have Neanderthal DNA?

Most people of non-African descent have some Neanderthal DNA, while African populations have little to no Neanderthal ancestry due to limited interbreeding in Africa. However, everyone shares a common ancestor with Neanderthals.